Outline of an Economic Model for an Inclusive Democracy

Takis Fotopoulos

Abstract This article takes for granted the fact that economic democracy, in the sense of the institutional framework securing the equal sharing of economic power, is a fundamental component of an inclusive democracy, that is, democracy in the political, economic, ecological and social realms (workplace, household, etc.). In this context, the double aim of the article is to examine the institutional framework of economic democracy and the transitional economic strategy that would lead us to an inclusive democracy.

Institutional Restructuring for Economic Democracy

Although it is up to the citizens’ assemblies of the future to design the form an inclusive democracy will take, I think that it is important to demonstrate that such a form of society is not only necessary, so that the present descent to barbarism can be avoided, but feasible as well. This is particularly important today when the self–styled ‘left’ has abandoned any vision of a society that is not based on the market economy and liberal ‘democracy’, which they take for granted, and has dismissed any alternative visions as ‘utopian’ (in the negative sense of the word). It is therefore necessary to show that it is in fact the ‘Left’s’ vision of ‘radical’ democracy which, in taking for granted the present internationalised market economy, may be characterised as utterly unrealistic. But, I think it is equally important to attempt to outline how an alternative society based on an inclusive democracy might try to sort out the basic socio–economic problems that any society has to deal with, under conditions of scarce resources and not in an imagined state of post–scarcity. Such an attempt may not only help supporters of the democratic project form a more concrete idea of the society they wish to see but also assist them in addressing the ‘utopianism’ criticisms raised against them.

Participatory Planning and Freedom of Choice

The major problem that an alternative economic organisation based on an inclusive democracy faces is how to achieve an allocation of scarce resources that meets the needs of all citizens and at the same time secures freedom of choice. Here, we may distinguish between two main types of proposals: a) the socialist–statist proposals, which take for granted the present institutional framework of the internationalised market economy and aim to enhance the institutions of ‘civil society’ so that political and economic power can be counterbalanced by autonomous (from the state and the market) movements and institutions; and b) the libertarian–socialist proposals which fall under either worker–oriented models or community–oriented models.

A typical example of the ‘civil societarian’ approach is the proposal made by Hilary Wainwright, who, in the process of searching for “new forms of democracy,” argues that the real question about economic democracy is whether “there are mechanisms of economic coordination and regulation which allow an element of competition between self–managed enterprises, and which at the same time promote social and environmental goals arising from society–wide democratic processes in economic affairs.”[1] However, what the author means by ‘democratic processes’ has nothing to do with political and economic democracy, defined as the equal sharing of political and economic power respectively. All that is meant, as it becomes clear by the book’s eulogising of the ‘new economic networks’ (trade union committees, health and safety projects, initiatives for socially responsible fair trade, etc.), is “socialising the market through mechanisms embedded in independent democratic associations sharing practical knowledge, rather than the state.”[2]

The logic behind this proposal is that any scarcity society faces a problem of democratising knowledge and particularly economic knowledge, what economists usually call the ‘information flow’ problem. Hayek, Mises and other economists of the Right have long argued against the possibility of a planned socialist economy on the grounds that because of the nature of economic knowledge no administrative system can have all the information needed for efficient economic decision–taking. As Hayek puts it, “the economic problem of society is thus not merely a problem of how to allocate ‘given’ resources ... it is a problem of the utilisation of knowledge which is not given to anyone in its totality.”[3] He concludes that only an unregulated market, through a price mechanism providing correct signals of scarcities and desires, could efficiently produce the required information. In fact, it is this supposed efficiency of the free market that made the market, according to Hayek, a ‘spontaneous’ product of civilisation.

There is obviously no need to deal here with the historical distortions of Hayek[4] about the ‘spontaneous’ development of markets—a topic that I examined in Society and Nature,[5] nor with the ridiculous assumption that it is state regulations and social controls that ‘distort’ prices and not the built–in trend in any market economy toward the concentration of economic power, which then invites social controls to check it. Therefore, if, as I have attempted to show elsewhere,[6] both central planning and the market economy inevitably lead to the concentration of power, then neither the former nor the latter can produce the sort of information flows and incentives which are necessary for the effective functioning of any economic system. It is therefore only through genuine democratic processes, like the ones involved in an inclusive democracy, that these problems may be solved effectively.

Still, socialist statists of the ‘civil society’ tendency, acknowledging this problem of knowledge, end up with proposals to create independent–from–the–state democratic organisations and to ‘socialise’ the market “through a public process of price formation in which social and environmental considerations would be central.”[7] In other words, disregarding all History to date, they still suggest the ‘socialisation’ of the market economy! However, as shown below, it is possible to devise a truly democratic process of economic decision–taking, namely, a system that may combine an inclusive democracy and planning on the one hand and freedom of choice on the other. But, such a system has to assume away what ‘civil societarians’ take for granted: a market economy and a ‘statist’ democracy.

As regards the proposals of the libertarian–socialist Left, it can be argued that worker–oriented models cannot provide a meaningful alternative vision of society for today’s conditions: first, because such models usually express only a particular interest, that of those in the workplace, rather than the general interest of citizens in a community; and second, because the relevance of such worker–oriented models (like that of Castoriadis’[8] model for workers’ councils which represents perhaps the most elaborate version) is very limited in today’s post–industrial society. This is why community–oriented models offer, perhaps, the best framework for integrating workers’ control and community control, the particular and the general interest, individual and social autonomy.

However, there is a recent proposal for ‘participatory’ planning which, although it is not based on a community–oriented model, still, can reasonably claim that it expresses the general rather than the particular interest. Thus, Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel[9] have put forward an elaborate model of participatory planning in which the allocation of resources takes place through two types of councils: worker’s councils and consumers’ councils. These councils, working at various levels (from neighbourhood up to the national level), would determine production and consumption respectively, through an elaborate planning process which would start with every citizen formulating individual work and consumption plans that would then be aggregated and adjusted by means of a series of ‘iterations’.

But, although participatory planning does represent a significant improvement over the usual type of socialist planning proposals and it does secure a high degree of decentralisation, serious reservations may be raised about its feasibility as well as its desirability. As regards its feasibility first, the problem that arises here concerns also any kind of democratic planning which is not market–based. Any such planning has to involve an arbitrary and ineffective way of finding out what future needs will be (the information–flow problem)—a problem particularly crucial for non–basic needs. The notion suggested by supporters of planning, including Albert and Hahnel, that people’s needs can be discovered very easily “just by asking them what they want,” in fact, as was pointed out by Paul Auerbach et al., “flies in the face of decades of evidence both from East European planners and from marketing experience in the West.”[10] Even more important are the reservations about the desirability of such a model. Not only does it involve a highly bureaucratic structure that can be aptly characterised as ‘participatory bureaucracy’ and which, together with the multiplicity of proposed controls to limit people’s entitlement to consume, “would lay the ground for the perpetuation or reappearance of the state,”[11] but, to my mind, it also involves a serious restriction of individual autonomy in general and freedom of choice in particular.

This becomes obvious, given the principles the authors state should guide consumption decision making. Prominent among the three principles mentioned is that “decisions about what individuals wish to consume will be subject to collective criticism by fellow council members with specific guarantees for preserving individual freedoms and privacy [emphasis in original].”[12] Although the proviso about ‘guarantees’ is an obvious attempt by the authors to disperse any impression of Maoist totalitarianism given by this principle, still, the meaning of the principle is sufficiently clear. To my mind, the reason for this creeping totalitarianism is the fact that the model does not make any distinction between basic needs, which obviously have to be met in full, and non–basic needs, which in a democratic society have to be left to the citizen’s freedom of choice. The result of not drawing this important distinction is that the authors end up with a system where each citizen’s consumption, production and workload has, ultimately, to conform to the “average.” (“If a person did request more than the average, she might be questioned, and if her answers were unconvincing, she would be asked to moderate her request.”[13])

Coming now to the community–oriented models, the main recent proposal for a community–based society is the one offered by Confederal Municipalism. However, the proposals for Confederal Municipalism do not offer a mechanism for allocating resources which, within the institutional framework of a stateless, moneyless and marketless economy and under conditions of scarcity, will secure: a) the satisfaction of basic needs of all citizens, and b) freedom of choice. Confederal Municipalist proposals usually seem to imply a post–scarcity society in which an allocation mechanism is superfluous. Thus, Murray Bookchin points out that:

confederal ecological society would be a sharing one, one based on the pleasure that is felt in distributing among communities according to their needs, not one in which “cooperative” capitalist communities mire themselves in the quid pro quo of exchange relationships.[14]

Alternatively, some supporters of Confederal Municipalism seem to presuppose a ‘scarcity society’ and support an allocation mechanism based on democratic planning. Thus, Howard Hawkins argues that:

[w]hile self–management of the day–to–day operations by the workers of each workplace should be affirmed, the basic economic policies concerning needs, distribution, allocation of surplus, technology, scale and ecology should be determined by all citizens. In short, workers’ control should be placed within the broader context of, and ultimately accountable to, community control.[15]

However, such a model, although it may secure a synthesis of democracy and planning, does not necessarily ensure freedom of choice. In fact, all models of democratic planning (either of the worker–oriented or community–oriented variety) which do not allow for some sort of synthesis of the market and planning mechanisms do not provide a system for an effective exercise of freedom of choice. The issue therefore is how we can achieve a synthesis of democratic planning and freedom of choice, without resorting to a real market, which would inevitably lead to all the problems linked with a market allocation of resources. In the next section, a model which combines the advantages of the market (in the form of an artificial ‘market’) with those of planning is outlined.[16]

Outline of an Economic Model for Democracy

The proposed system here aims at a) meeting the basic needs of all citizens, and b) securing freedom of choice in a marketless, moneyless and stateless ‘scarcity–society’. The former requires that basic macro–economic decisions have to be taken democratically, whereas the latter requires the individual to take important decisions affecting his/her own life (what work to do, what to consume, etc.). Both the macro–economic decisions and the individual citizens’ decisions are envisaged as being implemented through a combination of democratic planning and an artificial ‘market’. But, while in the ‘macro’ decisions the emphasis will be on planning, the opposite will be true as regards the individual decisions, where the emphasis will be on the artificial ‘market’.

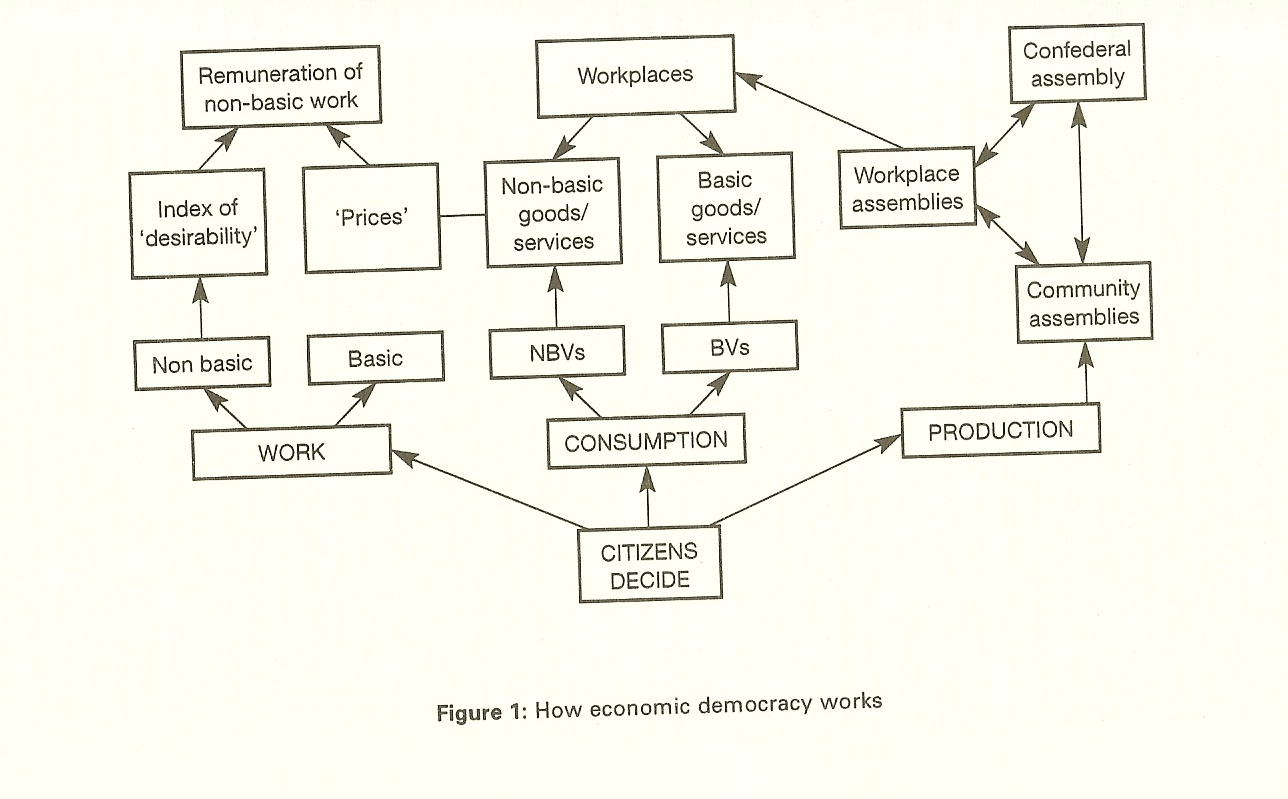

So, the system consists of two basic elements:

a ‘market’ element that involves the creation of an artificial ‘market’, which will secure a real freedom of choice, without incurring the adverse effects associated with real markets; and

a planning element that involves the creation of a feedback process of democratic planning between workplace assemblies, community assemblies and the confederal assembly.

The cornerstone of the proposed model, which also constitutes its basic feature differentiating it from socialist planning models, is that it explicitly presupposes a stateless, moneyless and marketless economy, which precludes the institutionalisation of privileges for some sections of society and the private accumulation of wealth, without having to rely on a mythical post–scarcity state of abundance. In a nutshell, the allocation of economic resources is made, first, on the basis of the citizens’ collective decisions, as expressed through the community and confederal plans, and, second, on the basis of the citizens’ individual choices, as expressed through a voucher system.

The main assumptions on which the model is based are as follows:

the community assembly—the classical Athenian ecclesia—at the municipality level is the ultimate policy–making decision body in each self–reliant community;

communities are confederated and their coordination is achieved through regional and confederal administrative councils of mandated, recallable and rotating delegates (regional assemblies/confederal assemblies);

productive resources belong to each community and are leased to the employees of each production unit for a long–term contract; and the aim of production is not growth but the satisfaction of the basic needs of the community, in a framework of freedom of choice, and those non–basic needs for which members of the community express a desire and are willing to work extra for. In this context, efficiency takes on a new meaning, implying effectiveness in satisfying human needs, instead of the usual meaning of minimising cost or maximising output in meeting money–backed wants.

As far as the meaning of needs is concerned, it is important to draw a clear distinction between, on the one hand, basic and non–basic needs and, on the other, between needs and satisfiers,[17] that is, the form or the means by which these needs are satisfied. Both these distinctions are significant in clarifying the meaning of freedom of choice in an inclusive democracy.

As regards, first, the distinction between basic and non–basic needs, it is clear that the rhetoric about freedom of choice in the West is empty. Within the framework of the market economy, only a small portion of the Earth’s population can satisfy whatever real or imaginary ‘needs’ they have, drawing on scarce resources and damaging ecosystems, whereas the vast majority of people on the planet cannot even cover their basic needs. But freedom of choice is meaningless unless basic needs have already been met. However, what constitutes a ‘basic’ need and how best it can be met cannot be defined in an ‘objective’ way. So, from the democratic viewpoint, there is no need to be involved in the debate between universalist and relativist approaches to needs.[18] In the framework of an inclusive democracy, what is a need, a basic need or otherwise, can only be determined by the citizens themselves democratically. Therefore, the distinction between basic and non–basic needs is introduced here because each sector is assumed to function on a different principle. The ‘basic needs’ sector functions on the basis of the communist principle: from each according to his/her ability to each according to his/her needs. On the other hand, the ‘non–basic needs’ sector is assumed to function on the basis of an artificial ‘market’ that balances demand and supply in a way that secures the sovereignty of both consumers and producers.

Second, as regards the distinction between needs and satisfiers, this distinction is adopted here not just because of the usual argument that it allows us to assume that basic needs are finite, few and classifiable and that, in fact, they are the same in all cultures and all historical periods. Although it may be true that what changes over time and place is not the needs themselves but the satisfiers, from our viewpoint, the distinction is useful for clarifying the meaning of freedom of choice. Today, there is, usually, more than one way of producing a good or service that satisfies a human need, even a basic one (types of clothing, etc.). So, freedom of choice should apply to both basic and non–basic needs. In fact, in an inclusive democracy, a priority decision that citizens’ assemblies will have to take regularly concerns the quantity and quality of satisfiers that satisfy basic needs. But, what is the best satisfier to meet each particular need should be determined individually by each citizen exercising his/her freedom of choice.

How can we create effective information flows about individual needs? The idea explored here involves the combination of a democratic planning process with a system of vouchers that could be used for the satisfaction of basic and non–basic needs. Thus, we could imagine the creation of a system in which there are two main types of vouchers: Basic Vouchers and Non–Basic Vouchers, all of them issued on a personal basis, so that they cannot be used, like money, as a general medium of exchange and a store of wealth.

Meeting the Basic Needs of All Citizens in the Confederation

Basic Vouchers (BVs) are used for the satisfaction of basic needs. These vouchers, which are personal and issued on behalf of the confederation, entitle each citizen to a given level of satisfaction for each particular type of need that has been characterised as ‘basic’, but do not specify the particular type of satisfier, so that choice can be secured. To ensure consistency as regards basic needs satisfaction throughout the confederation, the definition of what constitutes a basic need, as well as the level at which it has to be satisfied, should be determined by the confederal assembly, on the basis of the decisions of the community assemblies and the available resources in the confederation.

The overall number of BVs that are issued is determined on the basis of criteria which satisfy both demand and supply conditions, at the confederal level. Thus, as regards demand, planners could estimate the size and mix of it on the basis of the size of the population of the confederation, the size of the `basic needs’ entitlement for each citizen and the ‘revealed preferences’ of consumers as regards satisfiers, as expressed by the number of vouchers used in the past for each type of satisfier. As regards supply, planners could estimate, on the basis of technological averages, the production level, the mix and the resources needed, including the amount of work that each citizen has to do. Thus, every member of the community, if s/he is able to work, would have to work a ‘basic’ number of hours per week, in a line of activity of his/her choice, to produce the resources needed for the satisfaction of the basic needs of the community.

Draft plans could then be drawn on the basis of these estimates, and the confederal assembly could select, on the basis of the decisions of the community assemblies and workplace assemblies, the plan to be implemented and the implied amount of resources needed for its implementation. Each citizen would then be issued a number of BVs according to the special ‘category of need’ to which s/he belongs. Thus, the confederal assembly would determine a list of categories of basic needs for each section of the population using multiple criteria, including sex, age, special needs and so on. Then, in cases where this ‘objective’ allocation of BVs had to be amended to take into account personal circumstances, the community assemblies could make appropriate adjustments.

As regards the needs of the elderly, children and disabled, those unable to work are entitled to BVs in exactly the same way as every other citizen in the confederation is. In fact, one might say that the BVs scheme represents the most comprehensive ‘social security’ system that has ever existed, as it would cover all basic needs of those unable to work, according to the definition of basic needs given by the confederal assembly. It is also up to the same assembly to decide whether, on top of these BVs, Non–Basic Vouchers (see next section) would be allocated to those unable to work. As far as the supply of caring services is concerned, if caring is classified as a basic need—as it should be—then every member of the community should be involved in the provision of such services (and be entitled to BVs)—a significant step in the direction of establishing democracy in the household.

Meeting the Non–Basic Needs of All Citizens in the Community

Non–Basic Vouchers (NBVs) are used for the satisfaction of non–basic needs (non–essential consumption) as well as for the satisfaction of basic needs beyond the level prescribed by the confederal assembly. NBVs, like BVs, are also personal but are issued on behalf of each community, rather than on behalf of the confederation. Work by citizens over and above the ‘basic’ number of hours is voluntary and entitles them to NBVs, which can be used towards the satisfaction of non–essential needs. However, while with basic needs there should be no discrepancies in the degree of their satisfaction, so that the basic needs of all citizens in the confederation are met equally (as they should in an economic democracy), there are no corresponding compelling reasons for an equal satisfaction of non–basic needs across the confederation. In fact, community coverage of non–basic needs is just an extension of the individual citizen’s freedom of choice. Therefore, if in a particular community people wish to put more or less work in for the production of non–basic goods and services, they should be free to do so.

However, the system should be organised in such a way so that differences among communities as regards non–essential consumption should reflect only differences in the amount of work involved and not differences in the area’s natural endowments. A basic guiding principle should be that the benefits from the natural endowments of the confederation as a whole, irrespective of their geographical location, should be distributed equally among all communities and regions. This principle should apply to both basic and non–basic needs satisfaction so that no regional inequities may be created, other than those due to the amount of work involved.

With technical progress, one could expect that the satisfaction of non–essential needs will become increasingly important in the future—a fact confirmed by statistical studies on consumption patterns in the West that show a verifiable trend of basic–needs saturation.[19] Correspondingly, remuneration will take more and more the form of NBVs. There is, therefore, a double economic problem with respect to NBVs. First, we need a fair measure to remunerate non–basic work and, second, we need a measure of valuing non–basic goods/services that will secure a balance between their supply and demand at the community level. The classical solution of expressing the value of goods and services in terms of ‘man’ hours (proposed by Proudhon and Marx among others), apart from the fact that it creates all sorts of problems about equivalence of various types of work, the ‘conversion’ of tools/equipment used into ‘man’ hours, etcetera, is also fundamentally incompatible with a libertarian society[20] and, as I will discuss below, with a system of allocation based on freedom of choice.

I would therefore propose that to avoid these problems and, at the same time, to achieve a balance of demand and supply that satisfies fairness criteria, we should introduce a kind of ‘rationing value’ in order to value non–basic goods/services. The market mechanism, as it is well known, represents rationing by price, something that, as we have seen, represents the most unfair way of rationing scarce resources, as, in effect, it means rationing by the wallet. What I propose is a reversal of the process, so that price by rationing takes place, that is, prices, instead of being the cause of rationing—as in the market system—become the effect of it. Thus, to calculate the ‘rationing value’ (and consequently the price, expressed in terms of a number of NBVs) of a particular good/service, planners could divide the total of NBVs that were used over a period of time (say, a year) to ‘buy’ a specific good or service over the total output of that particular good/service in the same time period. If, for instance, the confederal assembly has ruled that a mobile phone is not a basic good, then the ‘price’ of a mobile phone can be found by dividing the number of NBVs used over the past 12 months for the ‘purchase’ of mobile phones (say 100,000) over the total number of mobile phones produced in the same period (say 1,000) giving us a ‘price’ per mobile phone of 100 NBVs.

The problem that may arise in this system is that there may be a mismatch between demand and supply of particular non–basic goods and services. Thus, to continue with the example of mobile phones, the producers of mobile phones and of their components may wish to offer only a limited number of hours over their ‘basic’ number of hours of work. In fact, the problem may arise even if some of them are unwilling to offer extra work, given that their activity, along with many other activities in today’s societies, are done in the form of team work. In that case, the proposed system of artificial ‘prices’ will be set in motion. The ‘price’ of mobiles, expressed in NBVs, will rise and this will push up the corresponding rate of remuneration (see next section), attracting more work in this activity. Of course, labour constitutes only part of the resources used and the overall availability of other resources for this type of activity has to be determined at regular intervals by the community assembly.

This way, production reflects real demand, and communities do not have to suffer all the irrationalities of the market economy or of the socialist–central planning systems mentioned above. The artificial ‘market’ proposed here offers, therefore, the framework needed so that planning can start from actual demand and supply conditions (reflecting real preferences of consumers and producers) and not from abstract notions formed by bureaucrats and technocrats about what the society’s needs are. Also, this system offers the opportunity to avoid both the despotism of the market that ‘rationing by the wallet’ implies, as well as the despotism of planning that imposes a specific rationing: either this rationing is of an authoritarian type, decided by an elite of bureaucrats and technocrats, or of a democratic one, decided by majority vote in the community assembly.

It is obvious that the proposed system has nothing to do with a money economy or the labour theory of value. Both are explicitly ruled out in this scheme: the former, because money, or anything used as an impersonal means of exchange, cannot be stopped from being used as a means of storing wealth; the latter, because (apart from the problems mentioned above) it cannot be used as the basis for allocating scarce resources. The reason is that even if the labour theory of value can give a (partial) indication of availability of resources, it certainly cannot be used as a means to express consumers’ preferences. The inability of East European central planning to express consumers’ preferences and the resulting shortages that characterised the system were not irrelevant to the fact that it was based on a system of pricing influenced by the labour theory of value.[21] Therefore, the labour theory of value cannot serve as the basis for an allocative system that aims at both meeting needs and, at the same time, securing consumer sovereignty and freedom of choice. Instead, the model proposed here is, in fact, a system of rationing, which is based on the revealed consumers’ preferences on the one hand and resource availability on the other.

Still, a well–known ecosocialist had no difficulty very recently in comparing an earlier version of the above proposals[22] to the labour theory of value, in order to conclude that “Fotopoulos suggests a system of work vouchers (really a form of money based on the labour theory of money).... this is not a new idea, having been postulated by Skinner (1948) and tried in the American ‘Walden II’ community in the 1970s”![23] As it is clear from this statement, the critic is unaware of the fact that a money model is not compatible with a system of vouchers which, as I had stressed in my article, “all of them [are] issued on a personal basis, so that they cannot be used, like money, as a general medium of exchange and store of wealth.”[24] Furthermore, to any careful reader of the proposed system, it is obvious that it has nothing to do with the simplistic description of a utopian community and the primitive scheme of labour credits described by Skinner[25]—a scheme which does not provide for any freedom of choice, the division of needs into basic and non–basic ones, etcetera. Finally, only a gross misunderstanding of my proposal for economic democracy could make anybody find similarities between it and the hierarchical scheme of Walden II, extolled by Skinner, who has rightly been described by Noam Chomsky as “a trailblazer of totalitarian thinking and lauded for his advocacy of a tightly managed social environment.”[26]

Work Allocation

The proposed system of work allocation reflects the basic distinction we have drawn above between basic and non–basic needs.

Thus, as far as the basic needs sector is concerned, as it was pointed out above, covering basic needs is a confederal rather than a community responsibility. Therefore, allocation of resources for this purpose is determined by the confederal assembly. So, in case a community’s resources are inadequate to cover the basic needs of all citizens, the extra resources needed would be provided by the confederal assembly. A significant by–product of this arrangement would be a redistribution of income between communities rich in resources and poor communities.

Once the confederal assembly has adopted a plan about the level of basic needs satisfaction and the overall allocation of resources, the community assembly determines the sorts of work tasks which are implied by the plan, so that all basic needs of the community are met. As regards the specification of work tasks, we may adopt the proposal that Albert and Hahnel make about ‘job complexes’. So, wherever possible, specific jobs are replaced by job complexes which are described as follows by the authors:

A better option (than the capitalist and the co–ordinator approach) is to combine tasks into job complexes, each of which has a mix of responsibilities guaranteeing workers roughly comparable circumstances. Everyone does a unique bundle of things that add up to an equitable assignment. Instead of secretaries answering phones and taking dictation, some workers answer phones and do calculations while others take dictation and design products.[27]

In principle, therefore, the choice of activity will be an individual one. However, as the satisfaction of basic needs cannot be left either to the mercy of the artificial ‘market’ for BVs, or just to the benevolence of each citizen, a certain amount of rotation of work may have to be introduced in case individual choices about working activities in covering basic needs are not adequate to secure all necessary work. Rotation of work is suggested here as an exceptional means to balance demand and supply of work and not as an obligatory rule imposed on all citizens, as suggested by Albert and Hahnel. I therefore think that the creation of comparably empowering lives, which is secured by taking part in community and workplace assemblies, in combination with work in job complexes, does not need, as a rule, a system of job rotation which may create more resentment than benefit to the community. Hierarchical structures at work and in society in general will be abolished if citizens have equal power at workplace assemblies and at community assemblies and not if they are just rotated between jobs. As the authors themselves admit, rotation may not have the desired effect of balancing inequalities between plants (“hierarchies of power will not be undone by temporary shuffling.”[28]). It is clear that in order to decide what constitutes a hierarchical structure some subtle distinctions have to be made concerning the various types of authority, like the ones discussed by April Carter.[29] The possibility of rotating work is neither an element of a non–hierarchical structure nor, necessarily, an element of job equality.

As regards the allocation of work in the non–basic needs sector, I would propose the creation of another ‘artificial’ market which, however, in contrast to the capitalist labour market, would not allocate work on the basis of profit considerations, or, alternatively, on the basis of the instructions of the central planners, as in ‘actually existing socialism’. Instead, work would be allocated on the basis of the preferences of citizens as producers and as consumers. Thus, citizens, as producers, would select the work they wish to do, and their desires would be reflected in the ‘index of desirability’ I describe below, which would partially determine their rate of remuneration. Also, citizens, as consumers, through their use of NBVs, would influence directly the ‘prices’ of non–basic goods and services and indirectly the allocation of labour resources in each line of activity.

Therefore, the rate of remuneration for non–basic work, namely, the rate which determines the number of non–basic vouchers a citizen receives for such work, should express the preferences of citizens both as producers and consumers. As regards their preferences as producers, it is obvious that given the inequality of the various types of work, equality of remuneration will in fact mean unequal work satisfaction. As, however, the selection of any objective standard (e.g., in terms of usefulness, effects on health, calories spent, etc.) will inevitably involve a degree of subjective bias, the only rational solution may be to use a kind of ‘inter–subjective’ measure, like the one suggested by Baldelli,[30] that is, to use a ‘criterion of desirability’ for each kind of activity.

But, desirability cannot be simply assessed, as Baldelli suggests, by the number of individuals declaring their willingness to undertake each kind of work. Given the present state of technology, even if we assume that in a future society most of the high degree of today’s specialisation will disappear, still, many jobs will require specialised knowledge or training. Therefore, a complex ‘index of desirability’ should be constructed with the use of multiple rankings of the various types of work, based on the ‘revealed’ preferences of citizens in choosing the various types of basic and non–basic activities. The remuneration for each type of work could then be determined as an inverse function of its index of desirability (i.e., the higher the index, that is the more desirable a type of work, the lower its rate of remuneration). Thus, the index will provide us with ‘weights’ which we can use to estimate the value of each hour’s work in the allocation of NBVs.

However, the index of desirability cannot be the sole determinant of the rate of remuneration. The wishes of citizens as consumers, as expressed by the ‘prices’ of non–basic goods and services should also be taken into account. This would also have the important effect of linking the set of ‘prices’ for goods and services with that of remuneration for the various types of work so that the allocation of work in the non–basic sector may be effected in a way that secures balance between demand and supply. We could therefore imagine that half the rate of remuneration in the production of non–basic goods and services would be determined by the index of desirability and the rest be determined by the ‘prices’ of goods and services.

Of course, given that labour is only part of the total resources needed for the production of non–basic goods and services and that the non–basics sector is the responsibility of each community, in practice, problems of scarcity of various --other than labour --resources may be created. However, I think that such problems could be sorted out through a system of exchanges between communities similar to the one described below.

An important issue, raised by a penetrating examination of an earlier version of the above proposals,[31] refers to the specialist nature of some of the services needed for covering basic needs (doctors, teachers, etcetera) and the problems that their remuneration creates. Is it fair that “a highly trained healer would get only basic vouchers (BVs) to satisfy the basic needs of the community, while an artist would get non–basic vouchers (NBVs) for a few hours extra put in painting”?[32]

To answer this question, let’s see how the proposed system is supposed to work in some more detail:

First, the confederal assembly decides which needs are basic and which are not and presumably most (but not all) health and education services would be classified as ‘basic’.

Next, the same assembly would select a particular plan to be implemented that would which secure a balance between confederal demand and supply, as regards the satisfaction of basic needs. The plan would specify the number of hours of work and other resources needed in each type of activity, so that the basic needs of all citizens in the confederation would be covered.

Finally, citizens would choose individually the line of basic activity in which they wished to be involved.

It is obvious that for the types of activity which do not involve special training or knowledge there should be no problem of work allocation and remuneration. However, for lines of activity that require special training, knowledge, etcetera, a question of remuneration arises, given that most, if not all, of the work involved is ‘basic’. How then might the “doctor vs. artist paradox” be resolved? I think a solution to this sort of problem could be found in terms of specifying the part of basic work that does not involve any specialised training, etcetera, and the part which does (planners could easily estimate the relevant parts). Then, as regards the former, all work might be considered as ‘basic’ and entitle citizens to BVs only. The number of hours that each citizen will have to work on this type of activity will be determined according to the requirements of the plan adopted by the confederal assembly. However, as regards the latter, people engaged in activities requiring specialised training or knowledge could be entitled to NBVs, for each hour of ‘basic’ work done. Thus, a doctor, on top of his/her BVs, may receive a number of NBVs (determined on the basis of the index of desirability) for each hour of ‘basic’ work done. This way, the ‘doctor/artist paradox’ will not arise because a doctor will automatically get, apart from the BVs, a number of NBVs, whereas an artist—if his/her work is not considered by the assembly to be satisfying a basic need—will receive only BVs and as many NBVs as the number of hours s/he is prepared to work as an artist. On the other hand, if the confederal assembly considers the work of an artist as covering a basic need (as I think it should), then s/he will be entitled to NBVs, the number of which, however, will be determined by the index of desirability. Of course, the proposed solution involves a certain built–in bias in favour of specialised lines of activity but, given that in a complex society most activities do involve various degrees of specialised training and knowledge, I do not think this creates a serious problem—as long as the index of desirability accurately reflects the community’s preferences regarding the various types of work.

Production Targets and Technology

All workplaces, either those producing basic or non–basic goods and services, are under the direct control of workplace assemblies which determine conditions of work and work assignments. As regards production targets in particular, we have to distinguish between the various types of production.

Thus, as regards basic goods and services, the overall production targets for the confederation would be determined by the confederal assembly, in the procedure described above. The specific production levels and mix for each workplace would be determined by workplace assemblies, on the basis of the targets set by the confederal plan and the citizens’ preferences, as expressed by the use of vouchers for each type of product. Thus, production units could claim a share of the community resources that would be available (according to the confederal plan) for their type of production, which would be proportional to the vouchers offered to them by the citizens as consumers.

As regards non–basic goods and services, producers of non–basic goods and services would adjust at regular intervals their production levels and mix to the number of vouchers they received (i.e., to demand), provided, of course, that resources would be available for their type of activity. This implies that, apart from the confederal plan, there should be community plans addressing resource allocation in the non–basics sector; their main aim would be to give an indication of the availability of resources to workplace assemblies so that that they could determine their own production plans in an informed way that would avoid serious imbalances between supply and demand, as well as ecological imbalances. So, community planners, on the basis of past demand for particular types of non–basic goods, the projections for the future, the aim to achieve ecological balance as well as a balance between supply and demand, could make recommendations to the community assembly about possible targets with respect to available resources, so that the assembly could take an informed decision on a broad allocation of productive resources between various sectors. However, the actual allocation between production units would be on the basis of the demand for their products (shown by the NBVs offered to each unit for its product) and would take place directly between production units, and not through a central bureaucratic mechanism.

Finally, as regards intermediate goods (equipment, etc.), which are needed for the production of basic and non–basic goods, producers of such goods would arrange a product mix determined ‘by order’. Thus, production units of final goods would place orders with producers of intermediate goods on the basis of the demand for their own products and the targets of the plan. So, the confederal and community plans should also include targets for intermediate goods as well as decisions about the crucial question of resource allocation through time (resources to be devoted for community investment on infrastructure, for community research and development, etc.).

Finally, an important issue that arises with respect to production refers to the question of whether a new economic system based on economic democracy presupposes, in principle, the discarding of present technology which—as with any technology—is directly related to the social organisation in general and the organisation of production in particular. It is therefore obvious that the change in the aims of the economic system that the introduction of economic democracy implies will be embodied in the technologies that will be adopted by the community and workplace. Of course, this does not exclude the possibility that the new technologies might contain parts of the existing technology, provided that they are compatible with the primary aims of a community–based inclusive democracy.

In a dynamic economic democracy, investment on technological innovations, as well as on research and development in general, should constitute a main part of the deliberations of the confederated community assemblies. The advice of workplace assemblies, as well as that of consumers’associations, would obviously play a crucial role in the decision-taking process.

Distribution of Income

The effect of the proposed system on the distribution of income will be that a certain amount of inequality will inevitably follow the division between basic and non–basic work. But, this inequality will be quantitatively and qualitatively different from today’s inequality: quantitatively, because it will be minimal in scale in comparison to today’s huge inequities; qualitatively, because it will be related to voluntary work alone and not, as today, to accumulated or inherited wealth. Furthermore, it will not be institutionalised, either directly or indirectly, since extra income and wealth—due to extra work—will not be linked to extra economic or political power and will not be passed to inheritors, but to the community.

The introduction of a minimal degree of inequality, as described above, does not negate in any way economic democracy, which has a broader meaning that refers to equal sharing of economic power and not just to equal sharing of income. From this viewpoint, Castoriadis’[33] proposal for economic democracy suffers from a series of drawbacks arising from the fact that it assumes a money economy, as well as a real market which is combined with some sort of democratic planning. Money is still used as an impersonal means of exchange and a unit of value, although it is supposedly deprived of its function as a store of wealth, as a result of the fact that the means of production are collectively owned. However, although collective ownership of the means of production does stop money from being used as capital, nothing—save the use of authoritarian means—can stop people from using it as a means of storing wealth, creating serious inequalities in the distribution of wealth. Furthermore, the proposed system is based on the non–differentiation of salaries, wages and incomes—an arrangement which is not only impractical but undesirable as well. As I pointed out above, some diversity in remuneration as regards non–basic production is necessary to compensate for the unequal work satisfaction created by widely diverse types of work.

Exchanges Between Communities

Self–reliance implies not only an economic but also a physical decentralisation of production into smaller units, as well as a vertical integration of stages of production that modern production (geared to the global market) has destroyed. Therefore, the pursuit of self–reliance by each community will help significantly in balancing demand and supply. Still, as self–reliance does not mean self–sufficiency, despite the decentralisation, a significant amount of resources will have to be `imported’ from other communities in the confederation. Also, a surplus of various types of resources will inevitably be created that may be available for ‘export’ to the other communities.

These ‘exchanges’ refer to both basic and non–basic production. As regards the exchanges in basic goods and services, these would be taken care of by the confederal plan. Although most basic needs would be met at the community level, the resources needed for the satisfaction of basic needs would come both from the local community as well as from other communities. Also, the satisfaction of basic needs involving more than one community (e.g., transportation, communications, energy) would be coordinated through the confederal plan. So, as regards BVs, there should be no problem with respect to their exchangeability between communities.

But, as regards exchanges on non–basic goods, a problem of exchangeability of NBVs arises. This is because the satisfaction of non–basic needs is not part of the confederal plan, and the resources needed for these needs are basically domestic. Also, the valuation of non–basic goods and services will differ from community to community depending on available resources. Furthermore, a problem of regional inequities may arise because of the unequal geographical dispersion of natural endowments. Therefore, regional or confederal assemblies should determine a system of exchanging goods/services, on the basis of criteria that will take into account the geographical disparity of non–human resources. Finally, as regards exchanges of goods and services with other confederations (or countries still characterised by a market economy system), these might be regulated on the basis of bilateral or multilateral agreements.

To conclude, the above discussion should have made it clear that the double aim of meeting basic needs and securing freedom of choice presupposes a synthesis of collective and individual decision making, like the one proposed here in terms of a combination of democratic planning and vouchers. In fact, even if we were ever to reach the mythical stage when resources are not scarce, questions of choice would continue to arise with respect to satisfiers, ecological compatibility etc. From this point of view, the anarcho–communist position, which refers to a usufruct and gift economy, to the extent that it presupposes ‘objective’ material abundance, also belongs to the mythology of a communist paradise. This is an additional reason why the system proposed here offers a realistic model of how we may enter the realm of freedom in a scarcity society like the present one, with existing (municipalised) resources in each area, and given the constraints on them imposed by ecological requirements.

A Transitional Economic Strategy Towards an Inclusive Democracy

To my mind, the only realistic approach in creating a new society beyond the market economy and the nation–state, as well as the presently emerging new international statist forms of organisation, is a trasitional strategy that comprises the gradual involvement of increasing numbers of people in a new kind of politics and the parallel shifting of economic resources (labour, capital, land) away from the market economy. The aim of such a transitional strategy should be to create changes in the institutional framework and value systems that would at some stage replace the market economy, statist democracy, as well as the social paradigm ‘justifying’ them, by an inclusive democracy and a new democratic paradigm respectively.

So, the question that arises here is what sort of strategy can ensure the transition toward an inclusive democracy. In particular, what sort of action and political organisation can be part of the democratic project. In this problematique we have to deal with questions about the significance of struggles and activities which are related to every component of the inclusive democracy: the economic, political, social and ecological. A general guiding principle in selecting an appropriate transitional strategy is consistency between means and ends. It should be clear that a strategy aiming at an inclusive democracy cannot be achieved through the use of oligarchic political practices or individualistic activities.

Thus, as regards, first, the significance of collective action in the form of class conflicts between the victims of the internationalised market economy and the ruling elites, I think there should be no hesitation in supporting all those struggles which can assist in making clear the repressive nature of statist democracy and the market economy. However, the systemic nature of the causes of such conflicts should be stressed, and this task can obviously not be left to the bureaucratic leaderships of trade unions and other traditional organisations. This is the task of workplace assemblies that could confederate and take part in such struggles, as part of a broader democratic movement which is based on communities and their confederal structures.

Next, is the question of the significance of grassroots action in the form of education, or alternatively, direct action and activities like Community Economic Development projects, self–managed factories, housing associations, LETS schemes, communes, self–managed farms and so on. It is obvious that such activities cannot lead, by themselves, to radical social change. On the other hand, the same activities are necessary and desirable parts of a comprehensive political strategy, where contesting local elections represents the culmination of grassroots action. This is because contesting local elections does provide the most effective means to massively publicise a programme for an inclusive democracy, as well as the opportunity to initiate its immediate implementation on a significant social scale.

In other words, contesting local elections is not just an educational exercise but also an expression of the belief that it is only at the local level, the community level, that direct and economic democracy can be established today. Therefore, participation in local elections is also a strategy to gain power, in order to dismantle it immediately, by substituting the decision–taking role of the assemblies to that of the local authorities the day after the election is won. Contesting local elections gives the chance to start changing society from below, which is the only democratic strategy, as against the statist approaches which aim to change society from above. It is because the community is the fundamental social and economic unit of a future democratic society that we have to start from there to change society, whereas statists, consistent with their statist view of democracy, believe they have to start from the top, the state, in order to ‘democratise’ it.

But, setting aside the political aspects of the transitional strategy in the rest of the article, I will examine the economic aspects of it. As pointed out above, an economic strategy towards an inclusive democracy involves the gradual shifting of economic resources (labour, capital, land) away from the market economy. It also presupposes the elaboration of a comprehensive program of social transformation that explicitly aims at replacing the market economy and statist democracy with an inclusive democracy. Such a program should make clear why the taking over of several municipalities by a radical democratic movement could create the conditions for:

a drastic increase in the community’s economic self–reliance;

establishing a municipalised economic sector; and

the creation of a democratic mechanism to make economic decisions affecting the municipalised sector of the community, as well as decisions affecting the life of the community as a whole (local production, local spending, local taxes, etc.).

Thus, a comprehensive program for social change should make clear that citizens, for the first time in their lives, will have a real power in determining the economic affairs, albeit partially at the beginning, of their own community. All this, in contrast to today’s state of affairs where citizens supposedly have the power, every four years or so, to change the party in office and its tax policies but, in effect, they are given neither any real choice nor any way of imposing their will on professional politicians. This becomes obvious, for instance, if one looks at the economic programs of national parties which are expressed in such broad and vague terms that they do not commit politicians to anything concrete. Furthermore, as regards the spending of money collected by taxation, or borrowing, it is clear that people have no power at all to decide its allocation among different uses.

It is clear that the transitional stage contains features which would not be in the ultimate society. Many of the features, for instance, that constitute a transitional economic democracy will obviously not be components of future society. The inclusive democracy, as I described it above, is a stateless, moneyless, marketless society. On the other hand, the transitional strategy, taking for granted the statist ‘democracy’ and the market economy, aims to create alternative institutions and values that will lead to the phasing out of present hierarchical institutions and values.

In this context, the criticisms raised by David Pepper against an earlier version[34] of the proposals presented here are obviously out of place. Thus, Pepper claims that “Fotopoulos clearly advances a money economy: indeed all these components also feature in ‘mainstream’ green capitalistic economics.”[35] It is obvious that Pepper mixes up the economic features of a transitional strategy towards economic democracy, which I described in my article, with the proposal for economic democracy itself!

Self–Reliance in the Transitional Period

The question that arises here is how we can create the conditions for self–reliance today, that is, how can we help the transition from `here’ to `there’, from dependent to self–reliant communities. There is significant literature on local economic self–reliance[36] which can provide valuable clues for the steps to be taken in a transitional phase towards an inclusive democracy. Furthermore, lately, more and more local communities, which suffer the consequences of dependent decentralisation, are beginning to encourage local self–reliance through local initiatives to meet local needs with local resources.[37] However, all this literature, as well as the corresponding local efforts, aim to enhance self–reliance, taking for granted the market economy and the liberal democracy. On the other hand, a movement for an inclusive democracy has to develop a transitional strategy for a radical decentralisation of power to the municipalities with the explicit aim of replacing the present political and economic institutional framework. The following proposals may be taken as a contribution to this effort.

The basic preconditions for the increase in local economic self–reliance refer to the creation of local economic power, in the form of:

financial power,

tax power and, above all,

power to determine production.

As regards financial power, the establishment of a community bank network is necessary in this process. However, the establishment of such a network presupposes that the movement for an inclusive democracy and confederal municipalism has already taken over a number of municipalities. Still, even before this happens, there are a number of steps that can be taken in this direction. However, it should be stressed that such steps are bound to lead to marginalised projects unless effective power bases are created through contesting local elections and winning over municipalities. Such steps are:

Municipal Credit Unions (i.e., financial co–ops) could be set up to provide loans to their members for their personal and investment needs. One could also imagine the extension of the role of credit unions, so that the savings of members would be used for local development and social investment, in other words, for investment in local people to enable them to build up viable employment. This way, credit unions could become the basis on which a community bank network could be built at a later stage.

A local currency could play a crucial role in enhancing local economic self–reliance. This is because a local currency would make possible the control of economic activity by the community and, at the same time, could be used as a means for enhancing the income of the community members. The local currency does not replace the national currency but complements it. As a first step p resent LETS[38] schemes could be municipalised. Later on, a local credit card scheme could be created with the aim of covering the basic needs of all citizens. Thus, citizens may be issued free municipal “credit cards” in which the credit limit would be determined by income and wealth (i.e., the higher the level of income and wealth the lower the credit limit). These credit cards could be used for the purchase of locally produced goods and services. Such a scheme could therefore play a useful role in the transition to a voucher system that would replace all currencies in an inclusive democracy.

As regards taxing power, the transitional program for an inclusive democracy should involve steps for the shift of taxing power from the national to the local level, as a basic step in creating conditions of economic self–reliance. Then, a new local tax system could be introduced that could attempt to meet, as far as possible within the constraints of a market economy that would still exist in the transitional period, the basic principles of an inclusive democracy. Thus, a certain shift in the tax load should take place, away from taxing income and towards taxing wealth, the occupation of land, the use of energy and resources, as well as activities creating environmental and social costs for the community. The main goals of a local tax system should be:

the financing (with the help of the community banking system) of a program for the municipalisation of the local productive resources, which would provide employment opportunities for all citizens in the community;

the financing of a program for social spending that would cover the basic needs of all citizens, in the form of a basic income (its size would depend on the citizen’s income and wealth) guaranteed for every citizen, irrespective of ability to work;

the financing of institutional arrangements that would make democracy in the household effective;

the financing of programs for the replacement of traditional energy sources with local energy resources, especially natural energy (solar, wind, etc.) which would minimise both the dependence of local economies on outside centres, as well as the energy–related implications on the environment; and

the parallel economic penalisation of the anti–ecological activities of branches and subsidiaries of large corporations based in the community.

So, the combined effect of the above measures would be to redistribute economic power within the community, in the sense of greater equality in the distribution of income and wealth. This, combined with the introduction of the democratic planning procedures, should provide significant ground for the transition towards full economic democracy.

As regards the all–important power to determine production, comprehensive programs should be designed that will contain concrete proposals on the changes required in the economic structure of each municipality, so that the objectives of an inclusive democracy may be achieved. A transitional strategy towards greater self–reliance would involve people in the community producing more for themselves and one another, as well as substituting locally produced goods and services for goods produced outside the community. Financial incentives may be provided to local shopkeepers in order to induce them to stock locally produced goods and to citizens to buy them. This, in turn, would encourage local producers (farmers, craftsmen, etc.) to produce for and sell at the local market, breaking the chains of big manufacturers and distributors.

However, the creation of community enterprises in production or distribution would only have a political significance, in this transitional stage towards an inclusive democracy, if and only if they constitute part of a comprehensive political program towards radical social transformation. As Murray Bookchin puts it:

Removed from a libertarian municipalist context and political movement focused on achieving revolutionary municipalist goals as a dual power against corporations and the state, food co–ops are little more than benign enterprises that capitalism and the state can easily tolerate with no fear of challenge.[39]

Finally, a transitional strategy towards greater self–reliance should involve the shift to municipalities of important social services (education, health, housing, etc.) that have been moved initially to the state and now, increasingly, to the private sector. The same principle could be applied in connection with the provision of services (health, education, social services, etc.) where the use of local productive resources should be maximised, both in order to provide local employment and create local income and, also, to drastically reduce outside dependence. The municipalisation of services is particularly important today, when the welfare state is in ruins and is being gradually replaced by safety nets for the very poor and the parallel enhancement of private provision for the rest. A municipalised welfare system will not only be less prone to bureaucratisation but will also provide a much more effective mechanism than the state welfare system, as a result of its smaller size, its easier management and the targeted provision of services. Furthermore, as the municipalisation of social services will be part of a program to enhance individual and social autonomy, the effect will not be the creation of a new dependency culture.

The Transition to a Municipalised Economy

The creation of a municipalised economic sector is a crucial step in the transition to an inclusive democracy. The establishment, however, of self–managed productive units constitutes the foundation just for workplace democracy. What is also necessary for the creation of an economic democracy is the establishment of new collective forms of ownership that would ensure control of production, not only by those working in the production units, but also by the local community. The productive units could belong to the local economy and be managed by the workers working in those units, while their technical management (marketing, planning, etc.) could be entrusted to specialised personnel. However, the overall control of community enterprises should belong to the community assemblies which would supervise their production, employment and environmental policies. For instance, as a step in the transition to an economic democracy, community assemblies could decide to reduce drastically the wage differentials of people employed in community enterprises.

Hence, the new forms of organisation of production and collective ownership would not only create the preconditions for economic democracy, but also enhance the ‘general social interest’. This is in contrast to the particular interest that inevitably is being pursued by the social classes and groups of the hierarchically organised social systems. Therefore, the answer to the economic failure of socialist enterprises is not the neoliberal (with social–democratic connivance) privatisation of them but their municipalisation. The establishment of a series of community enterprises that belong to the municipality and are controlled by its citizens (through the community assemblies) in collaboration with the people working in them (through the workplace assemblies) would create local employment opportunities and expand local income under conditions that secure:

economic democracy in the sense of democratic participation in the running of these enterprises;

workplace democracy with no institutionalised hierarchical structures;

security of employment; and

ecological balance.

The two significant questions that arise with respect to the municipalisation of the economy in the transitional period are, first, how to establish such municipalised enterprises and, second, how to run them until they become parts of a full economic democracy—questions that I examined in the earlier version of the above proposals.[40] One point that I would like to add here is that an important condition that would differentiate community enterprises from the Mondragon–type of co–ops and turn them into truly transitional production units in the move to an inclusive democracy is that they should produce exclusively for the local market, with the use of local resources. If instead, they start producing for the broad market outside the community, as for instance the Mondragon co–ops are doing at the moment, then a process would be initiated that would end with their absorption into the market economy, even if formally they were still called co–ops. Thus, in the Mondragon case, as even an enthusiastic supporter of them observes, the competitive pressures created by Spain’s integration into the European Union have led to “strengthening the integration of co–op groups to make them more competitive with transnational competitors, expanding the highly successful retail co–op system beyond the Basque region in joint ventures with other co–ops and with non–profits that may not allow workers to become members immediately, increasing the maximum wage differential within co–ops to attract skilled technicians and managers”[41] and so on.

It is therefore obvious that for community enterprises to be successful they should be part of a comprehensive program to municipalise the economy—in other words, a program whose constituent elements are self–reliance, municipalised ownership and community allocation of resources. The aim of this process is to gradually shift more and more human and non–human resources away from the market economy into the new municipalised economy that would form the basis of an inclusive democracy. At the end of this process, the community enterprises would control the community’s economy and would be integrated into the municipalised sector of the confederation, which could then buy or expropriate privately owned big enterprises.

The Transition to a Confederal Allocation of Resources

The fundamental problem of the strategy leading to a confederal allocation of resources is how to create such institutional arrangements for economic democracy that are compatible with an institutional framework that is still a market economy. As the confederal allocation of resources was described in the first section of this article, the system involves two basic mechanisms for the allocation of resources: a) a democratic planning mechanism for most of the macro–economic decisions, and b) a voucher system for most of the micro–economic decisions. The voucher system, in effect, creates conditions of freedom of choice by replacing the real market with an artificial one. It is obvious that the voucher system cannot be introduced until a full economic democracy in the form of a confederation of municipalities has been introduced, although steps in this direction could be taken earlier, as described above. However, a democratic planning system could feasibly be introduced even in the transitional period although, obviously, its decision–making scope would be seriously constrained by the market economy. Still, it could play a useful role in educating people in economic democracy and at the same time in creating the preconditions for individual and social autonomy.

But, for any democratic mechanism to be significant and to attract citizens in the decision–taking process, it is presupposed that the decisions themselves are important. The case of classical Athens shows that, as long as this condition is met, it is perfectly feasible to attract thousands of people to exercise their civic rights. Thus, as Hansen observes, “the level of political activity exhibited by the citizens of Athens is unparalleled in world history, in terms of numbers, frequency and level of participation.... an Assembly meeting was normally attended by 6000 citizens (out of 30,000 male citizens over eighteen), on a normal court day some 2000 citizens were selected by lot and besides the 500 members of the Council there were 700 other magistrates.”[42] It is therefore crucial that during the transition to an inclusive democracy the municipality, that is, the demos, should be empowered with significant powers that would convert it into a coherent system of local taxation, spending and finance. Then, community assemblies (or neighbourhood assemblies, in big cities, confederated into community assemblies) could be empowered to make decisions affecting the economic life of the community, which would be implemented by the Town Council or other relevant body, after it has been converted into a body of recallable delegates.

Thus, the shift of tax power to the municipalities, which should be a basic demand of a new democratic movement, would allow community assemblies to determine the amount of taxes as well as the way in which taxes would be charged on income, wealth, land and energy use, as well as consumption. Community assemblies could, at annual intervals, meet and discuss various proposals about the level of taxation for the year to come, in relation to the way the money collected by the municipality should be spent. This way, community assemblies would in effect take over the fiscal powers of the state, as far as their communities are concerned, although in the transitional period, until the confederation of municipalities replaces the state, they would also be subject to the state fiscal powers.

Similar measures could be taken as regards the present state powers with respect to the allocation of financial resources. The introduction of a community banking system, in combination with local currencies, would give significant power to community assemblies to determine the allocation of financial resources in the implementation of the community’s objectives (creating new enterprises, meeting ecological targets, etc.).

Finally, assemblies would have significant powers in determining the allocation of resources in the municipalised sector of the community, namely, the municipalised enterprises and the community social services. As a first step, community assemblies could introduce a voucher scheme with respect to social services. At a later stage, when a significant number of municipalities have joined the confederation of inclusive democracies, community assemblies could expand the voucher system to cover basic needs of all citizens, at the beginning, in parallel with the market economy—until the latter is phased out.

In conclusion , nobody should have any illusions that the implementation of a transitional strategy toward economic democracy will not receive a hard time from the elites controlling the state machine and the market economy. However, as long as the level of consciousness of a majority in the population has been raised to adopt the principles included in a program for an inclusive democracy—and the majority of the population has every interest in supporting such a program today—I think that the above proposals are feasible, although of course there may be significant local variations from country to country and from area to area, depending on local conditions. Without underestimating the difficulties involved in the context of today’s all–powerful methods of brain control and military and economic repression that the state and market elites possess, I think that the proposed strategy is a realistic strategy on the way to a new society.

Figure 1: How Economic Democracy works

[1] Hilary Wainwright, Arguments for a New Left (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994), pp. 147–48

[2] Hilary Wainwright, Arguments for a New Left, p. 148.

[3] F. Hayek, Individualism and Economic Order (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1945/1949), pp. 77–78.

[4] For an effective critique of Hayek and the ‘libertarian’ Right, see Alan Haworth, Anti–Libertarianism, Markets, Philosophy and Myth (London: Routledge, 1994).

[5] See Takis Fotopoulos, “The Nation–State and the Market,” Society and Nature, Vol. 2, No. 2 (1994), pp. 37–80.

[6] Takis Fotopoulos, “The End of Socialist Statism,” Society and Nature, Vol. 2, No. 3 (1994), pp. 11–68.

[7] Hilary Wainwright, Arguments for a New Left, p. 170.

[8] Cornelius Castoriadis, Workers’ Councils and the Economics of a Self–Managed Society (Philadelphia: Wooden Shoe, 1984); originally published in Socialism ou Barbarie (“Sur le contenu du Socialisme,” Socialisme ou Barbarie, No. 22 [July–Sep. 1957]); and first published in English as a Solidarity pamphlet, Workers’ Councils and the Economics of a Self–Managed Society (London: Solidarity, 1972).

[9] Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, Looking Forward: Participatory Economics for the Twenty–First Century (Boston: South End Press, 1991).

[10] Paul Auerbach et al., “The Transition From Actually Existing Capitalism,” New Left Review, No. 170 (July/Aug. 1988), p. 78.

[11] John Crump, “Markets, Money and Social Change,” Anarchist Studies, Vol. 3, No. 1 (Spring 1995), pp. 72–73.

[12] Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, Looking Forward, p. 48.

[13] Michael Albert and Robin Hahnel, Looking Forward, p. 49.

[14] Murray Bookchin, From Urbanization to Cities: Toward a New Politics of Citizenship (London: Cassell, 1992 & 1995), p. 254.

[15] Howard Hawkins, “Community Control, Workers’ Control and the Cooperative Commonwealth,” Society and Nature, Vol. 1, No. 3 (1993), p. 60.

[16] For an earlier, limited version of this model, see Takis Fotopoulos, “The Economic Foundations of an Ecological Society,” Society and Nature, Vol. 1, No. 3 (1993), pp. 1–40.

[17] Paul Ekins and M. Max–Neef, eds., “Development and Human Needs” in Real Life Economics: Understanding Wealth Creation (London: Routledge, 1992), pp. 197–213.